Refined by time

The Quicksilver project was set up to resurrect the design process that created and developed Donald Campbell's legendary boat, Bluebird K7. Campbell had marked-up an unprecedented string of seven consecutive World Water Speed Record triumphs for Britain in the 1950s and 60s, but then came an abrupt ending with his death in 1967. The record passed to America and then Australia, but Britain wasn't entirely beat. Led by Bluebird's chief designer, Ken Norris, we revisited the principles of K7's original design and its subsequent years of evolution, with a specific view to developing a worthy successor.

What followed was a long-drawn-out and highly demanding quest to create a new boat. What would be a satisfactory configuration for this new craft? How might future Bluebirds have looked if Donald had lived? Three distinctly different concepts and many more sub-variants were evaluated before we finally settled on the definitive design.

No words of gratitude can sufficiently honour the late Ken Norris – pictured above, at centre – for leading this intensive research and design effort throughout a 12-year period of almost constant reassessment and change. Ken had not only co-designed Bluebird K7, but also Campbell's successful Bluebird CN7 World Land Speed Record car – he had little left to prove – and yet in the latter years of his life he had a yearning to understand more fully the lessons of the past and turn them into concepts for the future. He channelled it to a huge devotion of personal time and effort, almost all of which he invested in the Quicksilver project, which simply wouldn't have existed without him.

Indeed, the project was built around him.

Regarding the three earlier Quicksilver concepts, each described and illustrated below, each one had attributes to recommend it. Any of them might potentially have been successful, given sufficient work. But in the end we graduated to the design we have today – Concept 4 – which embodies the best aspects of its predecessors, combined with some fresh new principles. And tantalisingly, its configuration reflects Norris's thinking towards the end of his time with us, though others played key roles in defining it.

We did not intend such a time-consuming and difficult process, with so many different avenues explored. But a protracted period of evolution proved to be the only way of finding what we were searching for. And the experience gained stands us in good stead.

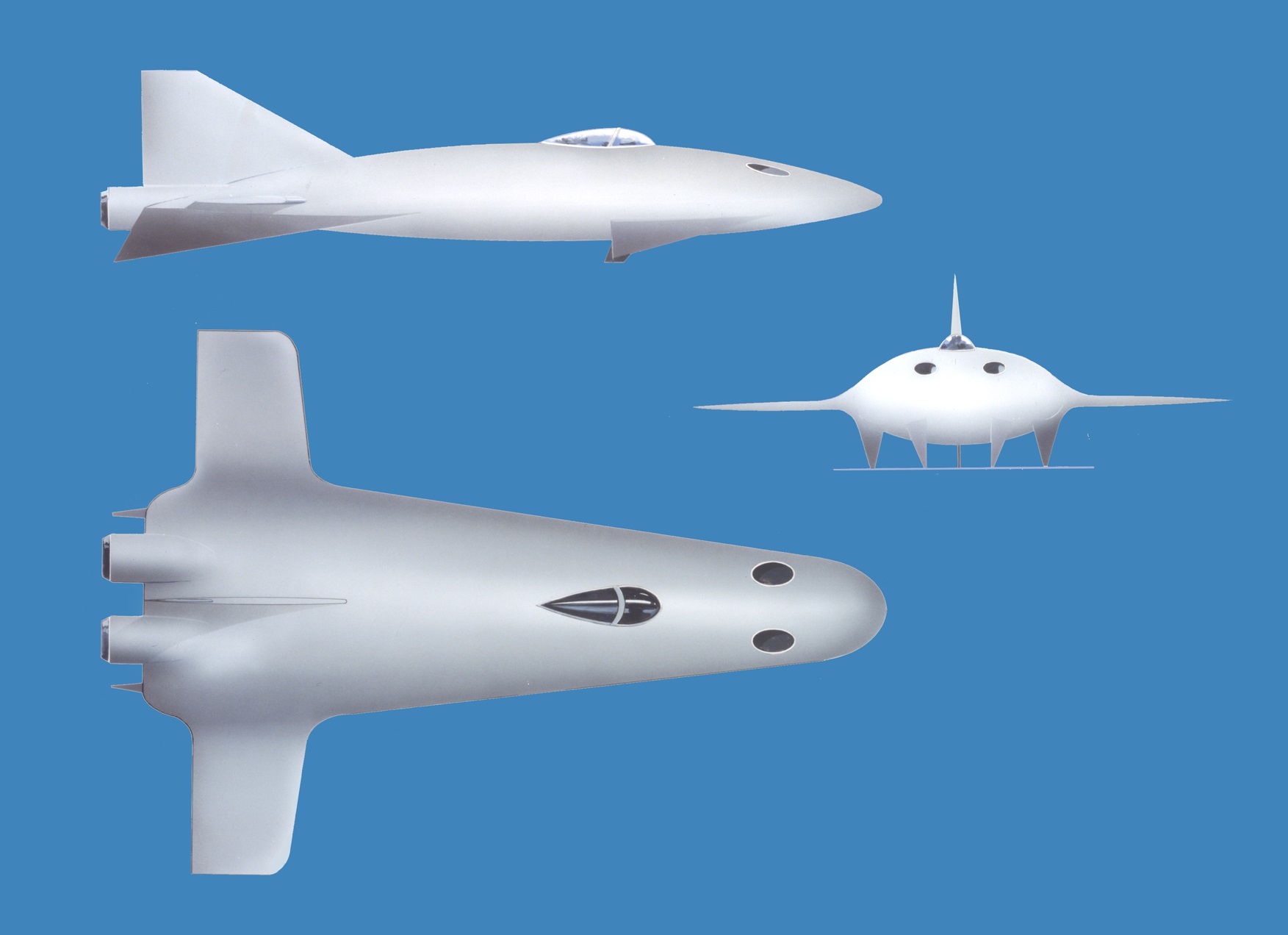

Concept 1

Ken Norris's original design concept for Quicksilver was tested in model form in great secrecy. A key feature was that it would have four planing surfaces, whereas before it had been customary for craft in this class to have three. The 'four-pointer' principle was central to Ken's philosophy, and it is a constant throughout Quicksilver's long design history.

Another novel aspect of the Concept 1 design is that its inspiration came from a car! The car in question was the Norris Brothers' four-wheel-drive Bluebird CN7, a record-breaker whose shape was designed to place an equal load on all four wheels at speed. The theory was that such a shape lent itself well to an ultra-high-speed boat, as it would be inherently stable in pitch.

Over a period of many years after Donald Campbell died, although the Bluebird project had ended, Ken Norris harboured the idea that his 'car-to-boat' concept might well have worked, had it been built as a successor to the boat in which Donald Campbell was killed. But it was only when Nigel Macknight approached him with the possibility of putting the theory into practice that Norris was able to find out. Macknight undertook to form a project around Norris, furnishing the resources to continue afresh, in keeping with Donald Campbell's own stated wish that the mission to keep key speed records in Britain's hands should not cease in the event of his own demise.

Unfortunately, it was found in extensive windtunnel tests to be impossible to achieve aerodynamic stability when the 'car-to-boat' theory was applied. This, in spite of numerous design modifications that were made to the test model, including the attachment of canards and the introduction of a huge butterfly-tail. The concept was therefore abandoned after three patchy years of study had been devoted to it.

But at least it was a start. For during those three years, Nigel decided on a name for the project:Quicksilver. And Macknight and Norris had formed a company, Quicksilver (WSR) Ltd., jointly owning a 100 percent shareholding. Furthermore, several other people joined the project to help it on its way.

A water-speed record team was in business, to continue where Campbell and Norris left off.

Concept 2

The second Quicksilver concept had only a relatively short period in favour. Ken Norris's approach this time was pragmatic. To build a boat almost identical to his very successful Bluebird K7, seven times a world speed-record holder, but this time having four planing surfaces instead of three, and with the sponson layout turned 'back to front'.

Contrary to a recent source stating that this concept was, "One of the design options for Bluebird K7," this was in fact a concept generated many years after K7's demise and crystallised during the early days of the Quicksilver project. The incorporation of four planing surfaces was the embodiment of Ken Norris's lessons from the operation of K7 and the accident that claimed it.

With the project continuing in strict secrecy, much of the boat's main hull structure was built, the fabrication work being carried out by racing-car specialist Bo Johansson. A Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour turbofan engine was acquired, together with a second Adour earmarked as a spare. But then the decision was taken to terminate construction.

A more ambitious development of this concept was what Ken had in mind next ...

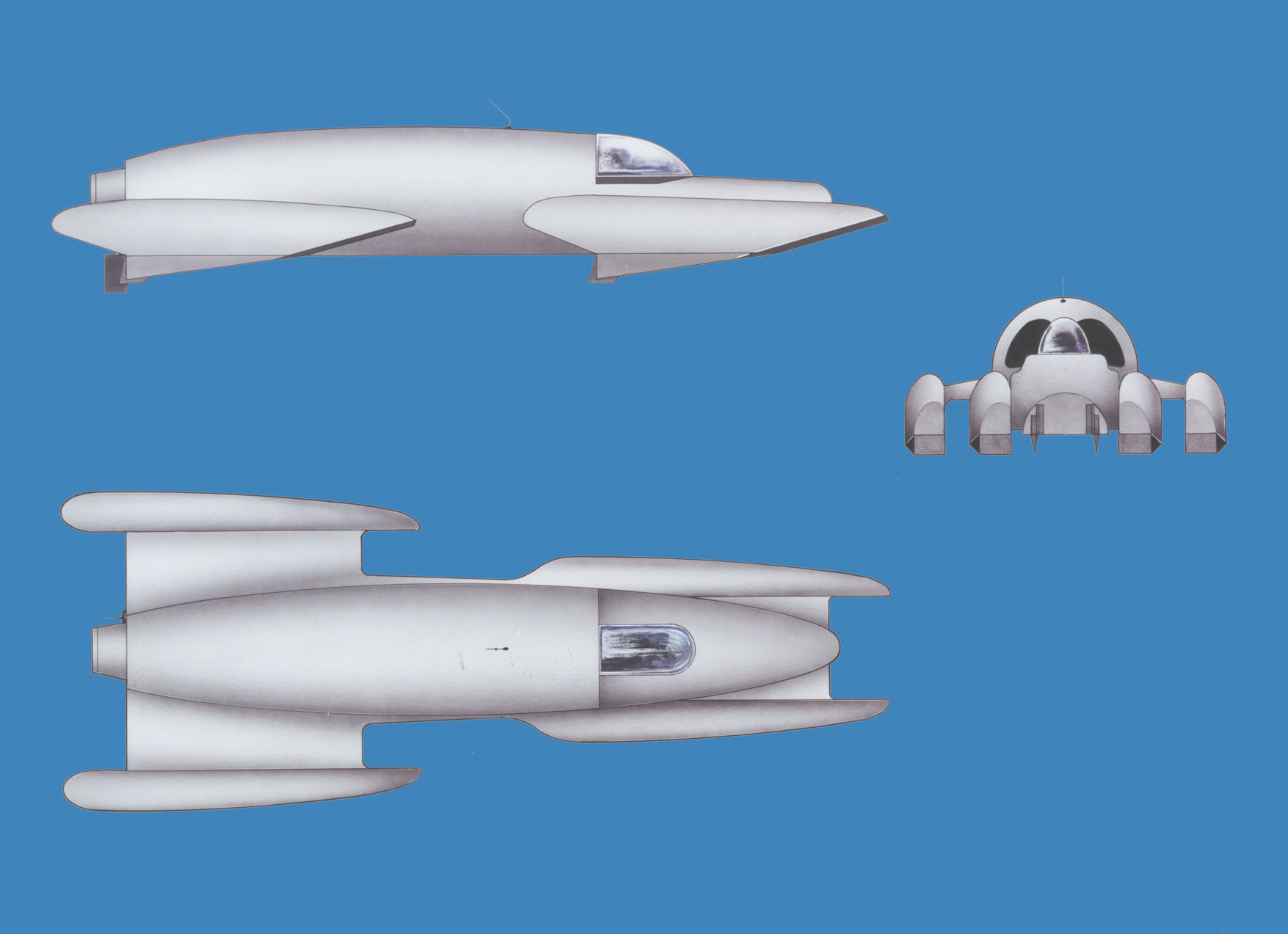

Concept 3

A 'four-pointer' like its predecessors, the third concept for Quicksilver occupied a huge amount of time, during which much refinement was made through successive rounds of windtunnel and towing-tank tests. It showed such great potential that finally its shape and basic details of its technical specification were publicly revealed. From that moment on, we shared our project with the world.

By this time, the Rolls-Royce Spey Mk.101 turbofan had been selected as its powerplant, and several of these engines had been acquired.

Construction got under way a short time later, but only after Ken Norris had been supplanted as chief designer and other designers started becoming involved. With so many fertile minds at work, it was perhaps inevitable that the project would take another direction. A search began for an even better concept, still incorporating many of Ken's design principles, and it was decided to use the unfinished Concept 3 boat as the basis for it.

But there was drama ahead. No sooner than work had got under way to alter the boat than the worse recession in living memory hit the economy like a wrecking-ball and Quicksilver (WSR) Ltd. – its income shrunk to a trickle as belts were pulled in all around – had to cease trading and the future looked bleak.

There was an equally dramatic rescue, however, when several team-members and sponsors banded together to purchase the assets of the doomed company and resurrect the necessary funding-streams. Now, under a new company, QWSR Ltd., work could continue before too much momentum was lost.

Concept 4

This is the definitive version of Quicksilver – the boat we are building today. Almost all of the hardware that had been built and acquired for the Concept 3 boat is being reused in the construction of Concept 4.

The 'four-pointer' arrangement continues, but with the sponsons relocated to the front due to the engine being mounted further forward in the hull than previously. A front-sponsoned layout was a development Ken Norris was considering towards the end of his time as the project's chief designer.

There are two cockpits – one in each sponson – as the forward positioning of the engine and improvements to the air-intake design leave insufficient space for a single, central cockpit. Overall, the shaping of the main hull and sponsons is far more complex than before, although the tailfin configuration is quite conventional.

While features from Ken Norris's involvement abound, Ron Ayers, Lorne Campbell, Mike Green and Roland Snell all had a hand in defining Concept 4.

Images © QWSR Ltd.